An international research team including staff members (Péter Ábrahám, Ágnes Kóspál, and Attila Moór) of the HUN-REN CSFK Konkoly Thege Miklós Astronomical Institute used the ALMA antenna array to capture the most detailed image ever of 24 debris disks, which may help better understand the turbulent adolescence of planetary systems.

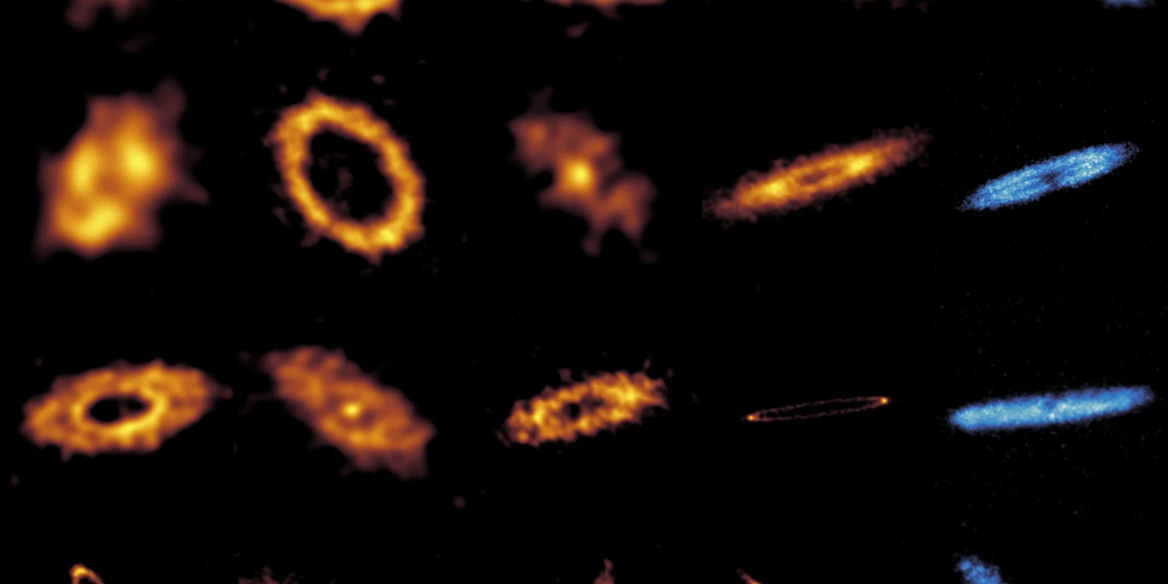

High spatial resolution ALMA images of the 24 debris disks studied in the ARKS program. The amber colors show the distribution of dust in the studied disks, while the blue show the distribution of carbon monoxide gas in the six gas-rich disks (their dust maps are shown in the column immediately to their left). Image credit: Sebastian Marino, Sorcha Mac Manamon, and the ARKS collaboration.

Missing pictures from the planetary systems' family album

The formation and early evolution of planetary systems takes place in gas-rich, planet-forming disks surrounding young stars. However, the disappearance of these disks does not mark the end of the planetary systems’ evolution. The newly formed planets may collide with each other, migrate from their original place of formation, or even leave their system before a more stable configuration is established. We can gain insight into similar events that took place in the early days of our Solar System by studying the structure of its outer debris ring, the Kuiper Belt.

Debris rings similar to the Kuiper Belt, but with a much larger mass, are also known to exist around other stars. In the Solar System we are most familiar with the largest components of the debris, the so-called Kuiper Belt objects (e.g., Pluto, Makemake, Haumea). In the exo-Kuiper belts, we can observe the thermal radiation of dust particles produced by collisions of larger bodies (planetesimals) that are invisible to us. This paves the way for the study of the structure of the debris disk and, thus, potentially the history of the specific planetary system.

While in the Solar System we are most familiar with the largest components of the debris, the so-called Kuiper Belt objects (e.g., Pluto, Makemake, Haumea), in the exo-Kuiper belts, we can observe the thermal radiation of dust particles produced by collisions of larger bodies (planetesimals) that are invisible to us, paving the way for the study of the structure of the debris disk and, thus, potentially the history of the specific planetary system.

Over the past decade, thanks to the ALMA antenna array, very detailed maps were obtained for many planet-forming disks, showing the spatial distribution of their dust and gas and revealing the environment of planets in their infancy. However, due to their 100-1000 times lower brightness, debris disks that bear witness to events during the adolescent phase have not yet been studied in similar detail.

The ARKS (ALMA survey to Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures) research team overcame this challenge and produced images of unprecedented detail of 24 debris disks using ALMA. The new, stunning images reveal complex disk structures with multiple rings, wide belts, sharp edges, unexpected arcs, and clumps. "We’re seeing real diversity—not just simple rings, but multi-ringed structures, wide belts, and strong asymmetries, revealing a dynamic and violent chapter in planetary histories,” adds Sebastián Marino, program lead for ARKS, and an Associate Professor at the University of Exeter.

Most important results and novelties of the ARKS program

- A New Benchmark: ARKS, as the largest and highest spatial resolution survey of debris disks, similarly to the DSHARP program which focused on planet-forming disks, represents a new level in this field.

- A Dynamic, Violent Youth: About one-third of observed disks show clear substructures (multiple rings or distinct gaps) suggesting legacy features left from earlier, planet-building stages or sculpted by planets over much longer timescales.

- Unexpected Diversity: While some disks inherit intricate/complex structures from their earlier years, others mellow out and spread into broad belts, similar to how we expect the Solar System to have developed/evolved.

- Clues to Planetary ’Stirring’: Many disks show evidence for zones of calm and chaos, with vertically ’puffed-up’ regions, akin to our Solar System’s own mix of serene classical Kuiper Belt objects and those scattered by Neptune’s long-ago migration.

- Surprising Gas Survivors: Several disks retain gas much longer than expected. In some systems, lingering gas may shape the chemistry of growing planets, or even push dust into wide belts.

- Asymmetries and Arcs: Many disks are lopsided, with bright arcs or eccentric shapes, hinting at gravitational shoves from unseen planets, leftover birth scars from planetary migration, or interactions between the gas and dust.

- Public Data Release: All ARKS observations and processed data are being made freely available to astronomers worldwide, enabling further discoveries.

Implications

The ARKS results show this teenage phase is a time of transition and turmoil. "These disks record a period when planetary orbits were being scrambled and huge impacts, like the one that forged Earth’s Moon, were shaping young solar systems,” says Luca Matrà, a co-PI on the survey, and Associate Professor at Trinity College Dublin.

By looking at dozens of disks around stars of different ages and types, ARKS helped decode whether chaotic features are inherited, sculpted by planets, or arise from other processes. Answering these questions could reveal whether our Solar System’s history was unique, or the norm.

Perspectives

The ARKS survey’s findings are a treasure trove for astronomers hunting for young planets and seeking to understand how planet families, like our own, are built and rearranged.

"This project gives us a new lens for interpreting the craters on the Moon, the dynamics of the Kuiper Belt, and the growth of planets big and small. It’s like adding the missing pages to the Solar System’s family album,” sums up Meredith Hughes, an Associate Professor of Astronomy at Wesleyan University and co-PI of this study.

The ARKS survey is the work of an international team of approximately 60 scientists, led by the University of Exeter, Trinity College Dublin, and Wesleyan University with the participation of Konkoly Observatory (HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences). For more information, visit https://arkslp.org/.

"This information was largely adapted from a press release shared by the U.S. National Science Foundation National Radio Astronomy Observatory." and link to https://public.nrao.edu/

Studies related to this topic have been published in the Astronomy & Astrophysics.